In search of lost time

Synchronisation in nature: a strange and magnificent phenomenon. Synchronisation in tech: a strange and debilitating nightmare. We have built 10 headsets equipped with LED lights and our goal is to trigger the lights perfectly in sync.

The real-time clock (RTC) hardware module we installed on our headsets in part 3 now comes seriously into play…

The hardware clock will help us maintain the date and time correctly for our headsets, so that they can be perfectly synchronised when they are told to start blinking at the same time. At least, in theory?

So then why are the blinking LEDs on the hats not synchronised?

Are we entering the stormy seas of distributed systems? Do we need to look into Leslie Lamport’s distributed clock synchronisation algorithm? Dive into another textbook by Tanenbaum? Or even worse, do we have to modify and recompile the Linux kernel on Raspberry Pi to make it a real-time kernel?

Thankfully not, thanks to a good system design. There will always be a central node which all headsets communicate with and could synchronise clock with, as well as one router to rule, I mean, route them all.

Our system lives at the strange boundary between real-time systems and non-real time systems. We define two lights as synchronised if they blink more-or-less within the same frame in a 24fps video. This is the equivalent of a ~40ms accuracy. With a deeper understanding of how Linux handles clocks, time protocols and time daemons, it looks like synchronisation within tens-of-miliseconds could be possible in our conditions even without a real-time kernel or any highly specialised tools.

This article is part of a series describing my collaboration with Hillary Leone on Synch.Live. To summarise, Synch.Live is a game in which of groups of strangers try to solve a group challenge, without using words. We will use a specially-designed headlamp, simple rules and a just-published algorithm to create the conditions for human emergence. A discussion about emergence and the goals of the project is in a previous article.

Instructions

- Build the player hat

- Set up the OS on the card - instructions & code

- Deploy configuration and software using Ansible - instructions & code

- Configure a time server on the router (a repository of router manuals may come in useful)

- Synchronise the clocks on the players using Ansible

To know more about how everything works, all the tools we’ve tried, and how we configured the time server on the router, then continue reading. Otherwise, for a quick setup, see the README files in the code repository.

A tale of two clocks

As our headsets run Raspberry Pi OS, a Linux distribution, the first step is to get familiar with how timekeeping works on Linux.

Linux has two types of clocks: hardware clocks and software clocks. The former is a battery-powered device which which runs independently of the operating system, in our case the RTC module, and can be configured in local time or universal time. We set it to universal time so we don’t have issues with timezones.

As the hardware clock is battery-powered, it will keep time even when the RPi is shut down.

The software clock, on the other hand, also known as the system or kernel clock, keeps track of time at the software level independently from the hardware clock. The kernel clock is usually updated from the hardware clock at every boot. Note that many RPis do not use a hardware clock module, so the kernel instead reads from a “fake” hwclock. In part 3 of this series, we have removed the lines from /etc/udev/hwclock which do that. (How this fake hwclock works is arcane and beyond the scope of this foray into clocks)

The kernel clock alwas shows universal time, and uses the timezone specified at the OS level.

$ timedatectl status

Local time: Sun 2021-04-11 23:06:43 BST

Universal time: Sun 2021-04-11 22:06:43 UTC

RTC time: Sun 2021-04-11 22:06:43

Time zone: Europe/London (BST, +0100)

System clock synchronized: yes

NTP service: active

RTC in local TZ: no

Local and universal time above come from the kernel clock, the RTC time matches the universal time, and the local time is correct with respect to the timezone.

To write or read the kernel clock, the command used in Linux is date, whilst for the hardware clock it’s hwclock.

To copy the time from the hardware clock to the software clock

$ sudo hwclock -s

To copy the time from the software clock to the hardware clock

$ sudo hwclock -w

But why would we need to ever copy the time from the software clock to the hardware, you ask?

Because even accurate RTCs have some drift. The best way to understand drift is that every million seconds, the clock will lag behind a number of seconds, which need to be accounted for. Unless one uses an atomic clock, it is realistic to assume that our small, battery powered, quartz-crystal based clock module will at some point drift more than our setup allows. But how much will inform our implementation.

The DS1307 RTC module

The timekeeping module we use for the headsets, the RTC Pi, uses a DS1307 crystal-based circuit. The crystal is not specified by the circuit diagram, but word around the internet is that it’s has a 20ppm accuracy. The accuracy of the clock depends on that of the crystal. Moreover, environmental conditions, such as temprature, will also cause frequency drift.

Clock accuracy is usually defined in terms of ppm, or parts per million. If a day has 86400 seconds, an accuracy of 100ppm will mean a drift of 8.64 seconds in a day. Thus for 20ppm, we expect about +-1.782 seconds of drift per day. As each circuit has its own idiosyncracies, we cannot expect the exact same amount of drift in all 10 devices. Ergo, running the experiment in two consecutive days without resynchronising the clocks will definitely result in desynchronised behaviour.

Therefore, not only does the system clock need to get synchronised to the hardware clock, but before each experiment, the hardware clock needs to be synchronised to the system clock.

Before this becomes a terrifying circular problem, the local (or global) network will come to rescue. Each large infrastructure company has their own time servers powered by way more sentive clocks than our little DS1307, and than more computers. And most operating systems provide protocols to handle clock synchronisation whenever a computer connects to a network.

Synchronising clocks

Time protocols

The most well-known time protocols are the Network Time Protocol (NTP), the Simple Network Time Protocol (SNTP) and the Precision Time Protocol (PTP). Each of them was created with different use-cases in mind, with NTP being the oldest and most generic.

NTP under best conditions can maintain time to within tens of milliseconds over the public Internet, and can achieve better than one millisecond accuracy in local area networks. NTP makes use of hierarchical strata of time servers, located in various areas in the world, and classified according to the network degree of separation from the clocks which are the source of time signals.

The first stratum 0 are hosted by countries or research institutes and powered by atomic clocks, national radio time broadcasts, or high-precision clock signals transmitted by GPS satellites. No stratum 0 packets are ever sent over the Internet; these super-high precision clocks are directly connected to stratum 1 devices via wired or satellite links, which then distribute the time to other clients over the Internet.

Stratum 1 devices tend to be made by commercial companies and are designed to connect to stratum 0 with high accuracy. Therefore there are not many publicly available stratum 1 servers to synchronise to.

Several thousand stratum 2 servers are publicly available and the NTP Pool Project aggregates them in pools grouped by geography. A client can access a pool in a certain country and the system will refer the client to the NTP server that is closest. Stratum 2 clients become stratum 3 servers when used to distribute time to other clients; if those clients have clients, they become stratum 4 and so on. The protocol supports 15 strata.

Stratum 16 is used to indicate that the server is not currently reliably synchronised with a time source.

To synchronise the system clock on a Linux system, for example with the UK stratum 2 pool, use ntpdate

$ sudo ntpdate 0.uk.pool.ntp.org

SNTP was created in the 90s as an lightweight alternative to NTP, but thankfully computers today no longer have the hardware limitations that once constrained the use of NTP. Both protocols can be used over wired or wireless networks and rely on the same hierarchical infrastructure.

PTP, introduced in 2002, relies on the same stratum 0 clocks and stratum 1 devices, but a separate hierarchy emerges. In contrast, PTP is a lot more precise than both NTP and SNTP, but it requires a wired connection and is not supported on RPi even using ethernet, as the controller does not support hardware timestamping.

The daemons of time

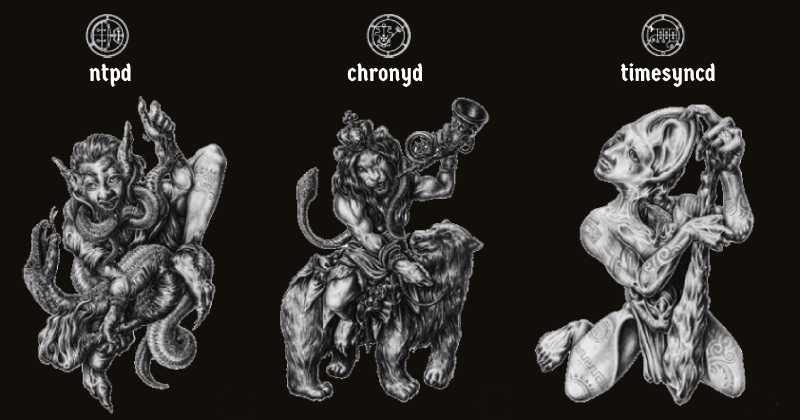

As time is serious system business, it is handled by a daemon - a piece of software which runs in the background and manages operating system functions. There are several daemons that deal with both fetching and setting system time, dark and mysterious enough that reading about them competes with a treatise on daemonology.

The canonical Linux implementation of NTP is ntpd.

There’s also xntpd, and timed, which as far as I can tell are closed-source implementations of NTP by IBM.

chronyd, another open-source option, has replaced ntpd in both Fedora 16 and Ubuntu 18.04. Both chronyd and ntpd are available for RPi.

Aside from chronyd, a timesyncd daemon has been added in systemd version 213. timesyncd is different from chronyd or ntpd insofar as it only implements the client side. This makes it lighter and less complex*.

Since timesyncd is already included in systemd, and thus in the Linux kernel, and is advertised as very lightweight, it seemed like the most natural starting choice. But after spending a couple of days dissecting it and setting it up, and wondering why there are up to one second differences between each of the headsets, it finally sank in that timesyncd is a SNTP client.

This has two drawbacks: first, by virtue of it being a client only, it requires an underlying NTP implementation - which brings us back to either ntpd or chronyd.

The second is that it’s an SNTP and not an NTP client. One of the practical outcomes of this is that it sets the time without disciplining it, and it lacks important features, such as the ability to instantaneously correct the time, to choose the best server from a pool, or to talk to hardware clocks.

Last, but not least, based on my tests, timesyncd cannot achieve acuracy much higher than 200ms even on a local network.

With both ptpd and timesyncd out of the way, the choice was between ntpd and chronyd. Reading the notes of its inclusion into Fedora, it became clear that Chrony is superior to ntpd due to both features and speed.

Although the choice of NTP and chronyd seems obvious now, it was not so when I first started dwelling into the arts of time synchronisation. On average, chronyd can synchronise with the same time server faster than the old ntpd service. This is what the developers claim as well as what I have observed when timestamping before and after the synchronisation with both daemons.

The Chrony package contains two utilities: chronyd, to be run as a service, and chronyc, a command line interface that can be used to adjust the time and to fetch drifts between the current device’s clock and chosen time servers.

Moreover, Chrony accounts and adjusts for unstable network connections and network latency, and is the recommended solution for devices that are not always online. Chrony never ever stops the clock, and never ‘jumps’ in time. The adjustments are made gradually, which is very useful to maintain a steady clock and incrementally remove that daily drift.

Last, but not least, chronyd can be setup to periodically sync back-and-forth with the hardware clock.

The time server

After running a few tests with the UK pool, it became clear that the latency introduced by the network may reduce precision below our desired ~50ms. Therefore, I started investigating how to run my own Chrony server.

We are not that interested in the clocks being accurate with respect to stratum 0, but more in how close the clocks of all the headsets are to each-other. Therefore, as our local server synchronised to the UK stratum 2 pool becomes a stratum 3 server, the headsets become stratum 4. From a global perspective they may be less accurate overall, but the fact that they synchronise to a server in the same network allows them to be more synchronised with each-other.

After playing with a Chrony server on my laptop, in preparation for installing it on the RPi 4 control centre / observer for the experment, it dawned on me that the router can be used as a time server. This will also allow the headsets and the observer to be on the same stratum.

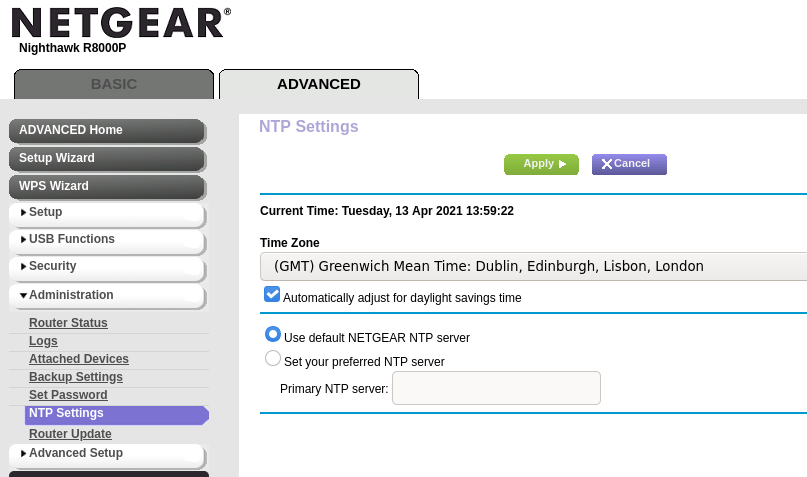

The Netgear router runs its own NTP server and synchronises the time with a Netgear NTP server (not sure if its stratum 1 or 2, but it doesn’t matter) every time it connects to the Internet successfully

To configure, go to Advanced > WPS Wzard > Administration > NTP Settings. I have since disabled daylight saving time.

I heard the community complain a lot about the firmware of this router, and apparently changing the timeserver causes issues. I don’t care what timeserver is used, as long as the same time is set on all my devices. Problematically, though, sometimes when the router is unplugged (which is likely with a system like this, which will be moved around to wherever we run the experiment), the time seems to be set to 1 Jan 1970. I haven’t had a chance to find a workaround, nor to reproduce this consistently. So far it remains a Heisenbug.

That aside, let’s say the NTP server on the router is enabled and running at the router’s IP address, 192.168.100.1. We install chrony on the headsets

$ sudo apt install chrony

and use chronyc from one of our headsets to check some information about this time server as well as how close the local time is to the server’s time:

$ chronyc -n tracking -h 192.168.100.1

Reference ID : 55C7D662 (85.199.214.98)

Stratum : 2

Ref time (UTC) : Tue Apr 13 14:06:57 2021

System time : 0.000061683 seconds slow of NTP time

Last offset : -0.000186714 seconds

RMS offset : 0.006821306 seconds

Frequency : 5.973 ppm fast

Residual freq : -0.110 ppm

Skew : 4.849 ppm

Root delay : 0.014099105 seconds

Root dispersion : 0.011558208 seconds

Update interval : 130.2 seconds

Leap status : Normal

We get a lot of information about the system time and how close the client’s clock is running to the server’s clock.

And from this we also find out the answer to an earlier question: if the router is a stratum 2 device, then the Netgear timeservers must be stratum 1. Nice.

Configuring the clients

To step closer towards the router’s clock, we use the command chronyc makestep. Chrony can be configured using /etc/chrony/chrony.conf, which will look something like this:

server 192.168.100.1 iburst

keyfile /etc/chrony/chrony.keys

driftfile /var/lib/chrony/chrony.drift

log tracking measurements statistics

logdir /var/log/chrony

rtcsync

makestep 1 -1

The most important lines here are the server line, which set the router’s NTP server as the server for the Chrony client on the RPi, the rtcsync line, which enables kernel syncrhonisation, every 11 minutes, of the real-time clock, and makestep 1 -1, which lets Chrony make any number of adjustments to the system clock until it’s in sync with the server, even if the adjustment is larger than a second. The latter configuration is useful because we have established to always sync the time before an experiment, and this may require ‘jumps’ or steps in time that are larger than a few miliseconds to be made at once.

The other settings are defaults.

We use Ansible to install chrony, copy off the chrony.conf file, and start the Chrony daemon on each headset. More on Ansible in part 4 of this series.

- name: Chrony setup

become: true

tasks:

- name: Make sure the chrony package is installed

apt:

name: chrony

state: latest

- name: Copy chrony.conf

copy:

src: etc/chrony/chrony.conf

dest: /etc/chrony/

owner: root

group: root

mode: 0644

- name: Start chrony service

shell: "systemctl start chronyd"

Note that having multiple NTP implementations may be problematic so I have also included a play in Ansible to remove all the NTPd related packages, such as ntpd, ntpdate and ntpstat.

Use systemctl to check if chronyd is running on the clients:

$ sudo systemctl status chronyd

We use Ansible to make calls to chronyc and chronyd to fetch time and correct any offsets, then to synch the hardware clock with the system clock.

- name: Sync time

become: true

tasks:

- name: Synchronise time with router's server

shell: "chronyc -n tracking; chronyc makestep"

- name: Synchronise hardware clock with system clock

shell: "hwclock -w"

And ta-da! Now all clocks should be in sync!

How do we check?

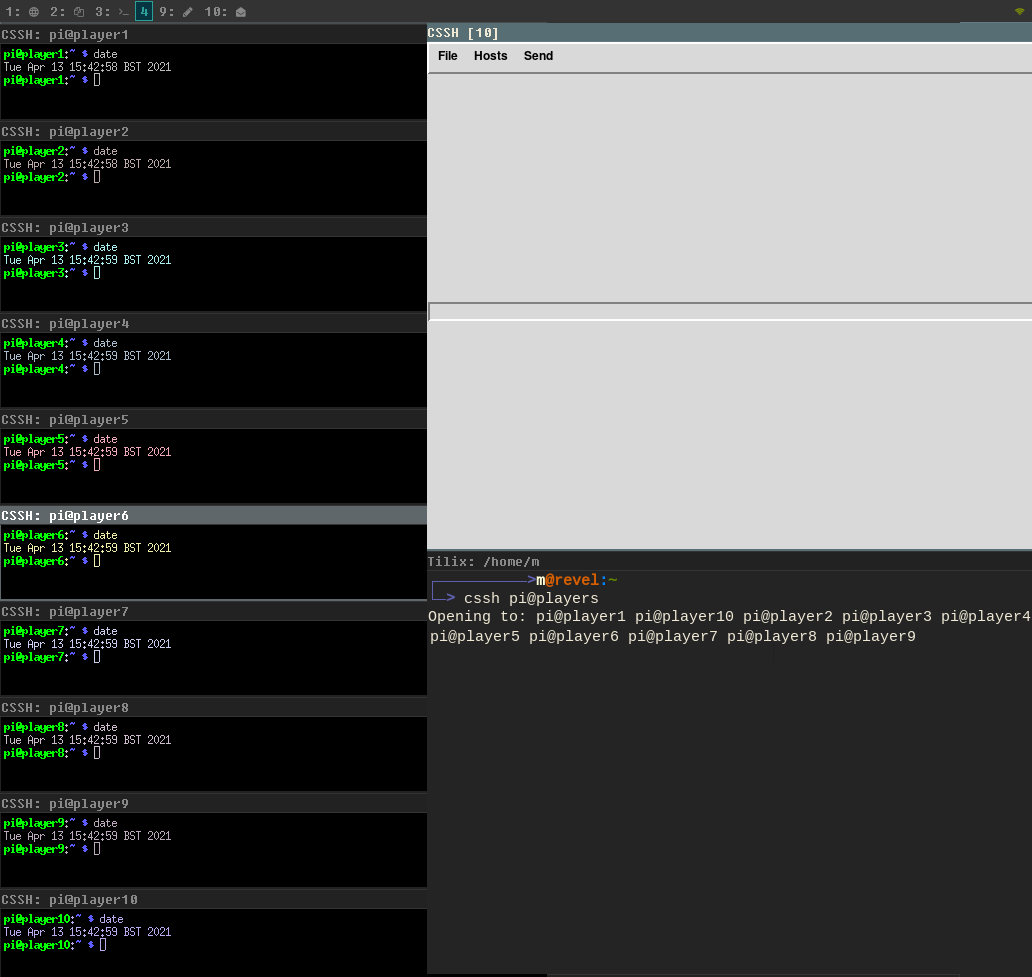

We could write some scripts that write the date to a file at certain times and then collect the logs and compare them, but a faster hack for this is a tool called clusterssh.

This tool allows opening simultaneous fast SSH connections to multiple devices and typing in the same command into all of them at once. The tool can be preconfigured using config files in the home folder in .clusterssh/. We are interested in the clusters file where we define a cluster called players for all our headsets using only their hostnames (assuming these are defined in /etc/hosts).

mkdir ~/.clusterssh

echo "players player1 player2 player3 player4 player5 player6 player7 player8 player9 player10" > ~/.clusterssh/clusters

Then run

$ cssh pi@players

and use the date command to fetch the date and check it is the same.

To get the date with milisecond precision:

$ date +%Y-%m-%d%H-%M-%S.%2N

Precision Scheduling

When I saw the date command spew out timestamps with less than 10ms variance, I thought I was done. I’m sure you thought you were done with this long-winded article with its ubertechnicalities and bad mythological humour. We were both dissapointed. Myself, by realising that the scheduling tool I know and love (to be read loathe), cron, is not accurate enough to start a task with second precision. This became more than obvious when I used Ansible to schedule a cron to start the mockloop.py routine from part 3 and it was clearly visible the lights were not even close to being in sync.

To my despair, I proceeded to hunt on Linux forums for a solution. Nothing obvious came my way; nobody has rewritten cron in Rust, nothing like that. cron seems to be doomed to be a minute-precision tool and for its intended purpose it makes most sense.

Python packages for scheduling showed up, but I won’t even go through them now, as each had its own drawbacks and would have made the codebase heavier for no particular reason. All along, a part of me kept denying the truth, and I told myself: there has to be a way of starting a damn task at a precise time in a single line of code in a Linux terminal.

In the end, I sorted it out with a little hack, using date and sleep and a while loop in bash. Every task is meant to start 10 seconds after the minute specified in the cron, and the loop fetches the system timestamp, checks if those 10 seconds have passed, and if not, sleeps for 50ms and tries again.

while [ "10" -gt "$(date +\%S)" ];

do /bin/sleep 0.05;

done;

python3 /home/pi/synch/mockloop.py

And ta-da! It worked!

We know the hats are now capable of synchronisation. The next step is to setup the observer with a Raspberry Pi Camera, and implement object detection and tracking for the pilot lights on the players.

Further reading

For more on clocks, see the Linux sytem administrator’s guide. For more on time daemons, see this article

Lamport’s distributed clock sync algorithm is explained in his paper Time, clocks, and the ordering of events in a distributed system (1978)

Tanenbaum Distributed Systems: Principles and Paradigms

A discussion of clock quality is available on the NTP project’s website

A group of researchers has implemented PTP on RPis and achieved milisecond accuracy, but the drawback is that kernel needs to be modified. See Performance Evaluation of IEEE 1588 Protocol Using Raspberry Pi over WLAN

A comparison of NTP implementations

A set of Ansible playbooks for time synchronisation is available on github

A Stack Exchange question discussing a similar application to ours, in which a hacker tries to take pictures at the exact same time with multiple Raspberry Pi