Synch.Live is an art experience designed to mobilize our hard-wired human instinct to cooperate.

Earlier this autumn, I was put in touch by my good friend Dr. P. with an artist whose ideas left a deep impression on me and resulted in what we hope to be a fruitful collaboration. Hillary Leone works at the intersection of art, science, technology and social impact.

Her newest work, Synch.Live, an interactive art installation inspired by emergent systems in nature, required the help of a computer scientist to build, as well as a multimedia professional to document, so A. and I jumped on board.

So what exactly is Synch.Live? Hillary explains it on her website as “an IRL game in which of groups of strangers try to solve a group challenge, without using words. We will use a specially-designed headlamp, simple rules and a just-published algorithm to create the conditions for human emergence and collective joy.”

The game takes inspiration from emergent systems in nature like flocks of birds or swarms of ants in which novel patterns emerge from collective effort. In these self-organizing systems, no single agent can do alone what the group can do together.”

“Here’s how we expect the experience will work: we gather a group of strangers to play the game in an open field, equip them with specially designed headlights, and invite them to solve a group challenge – without using words. The rules are simple: no talking, stay 2 meters apart, match your blinking lights with your neighbours, and keep moving. A cutting-edge algorithm calculates the extent of emergence in the group, as it’s happening in real time, and adjusts the frequency of the lights in response to the group’s behaviour.

Emergence occurs when the individual players figure out how to act as a group. Their headlights will suddenly start to blink on and off together like synchronous fireflies. And they probably won’t know exactly how they did it.”

As we build the hardware and software for this experiment, I shall document every step of our thinking process, research, and implementation. The remainder of this article explores the concept of emergence and its examples in nature, introduces the design goals and research questions, and presents an initial blueprint for the architecture of the Synch.Live system.

Emergence

First of all, what do we mean by emergence?

One of the oldest definitions comes from book VII of Aristotle’s Metaphysics, where he ponders on the nature of unity, or wholeness, and points out that many can act as one.

“… with respect both to definitions and to numbers, what is the cause of their unity? In the case of all things which have several parts and in which the totality is not, as it were, a mere heap, but the whole is something besides the parts, there is a cause…“

The concept and philosophy of emergence has a long history, which is deeply linked to both discussions of causality and philosophy of mind. It took more than two millenia, since Aristotle until today, to understand the importance of emergence, yet it’s still almost as mysterious today as it was then.

Emergence posits that physical phenomena are hierarchical, with properties and laws at the higher levels of the system that cannot be reduced to or derived from the lower levels. Perhaps the simplest example is water: there is nothing in the properties of either hydrogen or oxygen that would suggest that water is wet.

Emergence in nature

When looking at social groups in nature, certain insects, birds, and fish distinguish themselves by virtue of their ability to self-organise. Not only does their interaction manifest emergent patterns, but it does so without a leader or conductor.

Ant colonies reach consensus when trying to decide things such as whether they should move to a new nest by voting (with their feet!) When there is urgency, such as known danger or scarcity of resources, in order to accelerate the decision, the quorum threshold is lowered, so the decision can be made faster. All this behaviour is a result of very simple actions, and yet it’s so efficient that there is a whole field of computational optimisation based on ants. It has even been suggested that polarisation of political opinions happens with similar dynamics to consensus in ant colonies.

Emergent behaviour in nature appears in flocks of birds and schools of fish, manifesting itself in the complex patterns of their motion. A group of many individuals is seen to act as one entity, without any kind of leadership or macroscopic choreography. Starlings gather in groups of tens to hundreds of thousands of individuals to migrate and to hunt, a phenomenon known as murmuration.

Herrings gather in schools, swimming in the same direction on a coordinated way, to make foraging and migrating less dangerous. Sometimes schooling fish are even seen accompanying large predators.

Or, in Hillary’s words: “Like birds and ants, humans are hard-wired to synchronise and cooperate. Babies synchronise their heartbeats to their mothers, groups of strangers clap in unison, chant and sway together at sporting events, even synchronise their brainwaves with their neighbours at live concerts. In Synch.Live we hope to create the conditions for human emergence, by disabling language and mobilising our hard-wired instinct to cooperate.”

Measuring emergence

We can clearly observe emergent patterns with the naked eye, but measuring them is a very difficult task. First, we need to quantify or systematically describe the actions taken by the agents in the system. Then we need a framework to describe and quantify emergence.

Complexity science is concerned with such dynamical systems consisting of many interconnected components which exhibit emergent behaviour. As novel patterns emerge from collective effort, complexity science strives to provide the tools to identify their causal nature.

Exciting new work in complexity science and information theory strives to ‘reconcile emergences’ into a general framework. The researchers propose a criterion for the presence of emergence which takes into account causal relationships between the individual features of the system’s components and the macroscopic patterns that the system displays as the system evolves over time. For example, in a theoretical model for flocks of birds, if the individual features of the system are the spatial positions of each bird, there is a causal relationship between their position and the center of mass of the flock, treated as macroscopic feature. For Synch.Live, we aim to implement an algorithm which uses this same criterion to quantify emergence in the group motion of the players.

Modelling system behaviour

Our first aim is to produce a model of behaviour for the system we wish to study. Generally speaking, there are two large paradigms for modelling and reasoning about complex systems, which we can also apply to our exploration of the behaviour of a flock or a crowd:

1) Complex physical systems

Within this approach, the individuals in the system are treated as ‘particles’. The models are usually very simple, with the particles following local rules and evolving in discrete time steps.

Such a model that may inspire Synch.Live is the self-popelled particles model proposed by Vicsek. Each particle moves with the same absolute velocity, starting from a random position, and in a random direction. Every time step, each particle changes direction according to its neigbours, by following in their average direction at the next time step. A small random perturbation is added to each average direction to introduce chaos in the system. Depending on this pertubation parameter, the system may either stay disorganised, or become extremely organised. Below, the perturbation is slowly increased for a system of fixed density, absolute velocity and radius, and the behaviour of the particles becomes increasingly more chaotic. Emergence occurs at the threshold between order and disorder:

By introducing only two more spatial rules to the above model, we obtain the conditions for a somewhat realistic simulation of flocking birds. Reynold’s flocking model consists of bird-like objects (or ‘boids’) that move according to the following parametric rules:

- alignment, of their flight direction to that of their neighbours

- aggregation, or how much they tend to fly towards the center of the flock

- avoidance, or maintaining a distance from their closest neighbour

Simulations based on this model have been used for the wildebeests in Lion King and also the bats in Batman Returns.

The Reynolds model shows complex behaviour for a certain parameter range. If alignment and aggregation parameters are fixed, the avoidance parameter acts as a tuning parameter, akin to the amount of perturbation in Vicsek’s particles.

The emergence criterion that we will use in Synch.Live supports our qualitative intuition when applied to the Reynolds model. Only when the avoidance parameter is within a certain interval does the criterion confirm the existence of emergence.

2) Complex adaptive systems

This framework considers participants in the system as autonomous agents which sense the environment and make decisions according to it. Game theory in mathematics, actor-network theory in social sciences, and the social-force model for pedestrian crowds are a few examples that follow this paradigm and which we may explore in the future for better modelling of the Synch.Live experience. The complexity of each agent in the system makes these models difficult to describe and implement, but the results, when successful, are impressive.

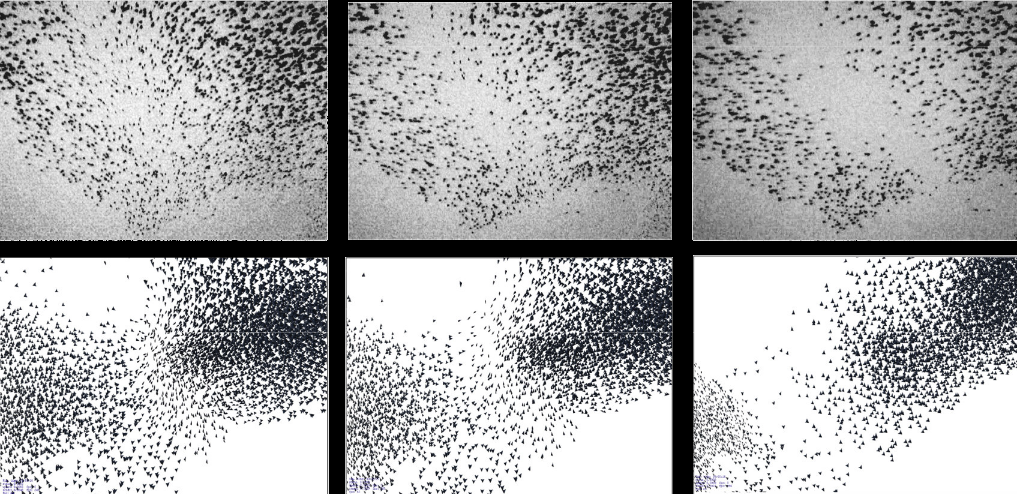

An example is a more realistic model for flocking starlings, which augments Reynolds’ flocking model with several extra features. Scientists were able to simulate some of the most complex patterns seen in the real system. The model extends the usual rules of local coordination with specifics of starling behaviour, mainly 1) their aerial locomotion, 2) a low and constant number of interaction-partners and 3) preferential movement above a ‘roosting area’.

The top row of images shows real-world footage of a flock captured by scientists in Rome. The bottom row are the outputs of the model from the original paper.

A stray thought: maybe disabling language in Synch.Live will allow us to consider a simpler model for the crowd dynamics. But whether successfully identifying emergence within the dynamics of a simplistic computer model will mirror onto the dynamics of the real players of Synch.Live is one of the exciting research questions we hope to tackle in this project.

The madding crowd

I cannot write about emergence without mentioning the canonical example: “mind from matter”. There is nothing in the individual neurons, that can suggest the richness of our conscious experience. And going one level higher: there is nothing in the individual human, that can suggest how society will evolve. Just look at nations, markets, the Internet.

“It would seem, at times, as if there were latent forces in the inner being of nations which serve to guide them.” ― Gustave Le Bon

Can Synch.Live help us understand these latent forces? Could we tap into the collective unconscious and learn about how emergence occurs in between humans? Our hypothesis is that just like birds flock together, humans could too, without words, without a leader. And when they do, they might also experience a different state of mind.

An interesting hypothesis comes from Carl Jung, when discussing the collective unconscious:

“A group experience takes place on a lower level of consciousness than the experience of an individual. This is due to the fact that, when many people gather together to share one common emotion, the total psyche emerging from the group is below the level of the individual psyche. If it is a very large group, the collective psyche will be more like the psyche of an animal.”

This project creates countless possibilities for new scientific questions. Can we apply existing crowd models to the Synch.Live experience? Can we measure emergence in a real world system? Now that we have a better understading of levels of consciousness and how to measure them, could we measure the level of consciousness of a group?

System design

Now how can we practically build Synch.Live? After a few meetings and brainstorming sessions, we had established a number of goals for the project.

To create the Synch.Live experience, we require a system which includes individual LED headsets worn by players, as well as a device which acts as observer, recording player motion, measuring the players’ dynamics in some way, and applying the emergence criterion. When emergence seems to increase, the players need to be informed through the behaviour of the lights.

Another very important goal besides creating the experience is creating a system that can be used for new science. We need the conditions for the game and future related experiments to be reproducible by other researchers. Therefore it is crucial that the system is as open and easy to deploy as possible. Therefore, we aim for the hardware solution to revolve around Raspberry Pis, and the software solution to be as much as possible tied to Python, as it has a very large community of scientists using it and a less steep learning curve than many other programming languages.

Since we want players to move freely, we need the headsets to connect to the network via Wi-Fi. To compute emergence and modify the behaviour of the lights in real-time, we require the observer to communicate with the individual headsets, and potentially also the headsets to communicate back.

Moreover, since the synchronisation of their lights is vital to the experience, we also need to make sure that each headset runs its own clock which does not drift for the duration of the experiment.

Hardware

For each headset, we aim to use:

- Raspberry Pi 0, as it is very light and small

- Real-Time Clock module, in order to make sure the clocks of the Pis are in sync and do not drift

- WS2801 LED strip with at least 20 LEDs

- portable battery and a USB power cable

- hat

For the observer, we require a camera to record the players moving, and a computer to extract information from the video stream, to compute emergence, and to communicate with the hats over the network. To maintain the project as open as possible, we decided to use:

- a Raspberry Pi camera module, which allows using interchangeable lens with the CCTV/8mm lens mount, as well as sports a decently sized sensor made by Sony (several times larger than a phone sensor)

- a set of two lens, a wide-angle 6mm and a 16mm

- a Raspberry Pi 4, the most performant Pi yet, which we will equip with a proper cooling fan to to best optimise it

The WiFi router needs to support tens of devices, as well as have a generous range, and high bandwidth. We decided on a sexy tri-band Netgear Nighthawk X6S, which supports up to 55 devices over a range of a few hundred square meters.

Software

The operating system installed on the Pis is the usual Raspbian, and the implementation uses Python 3, which ships with Raspbian. The majority of Raspbery Pi sensors and peripherals come with Python packages, such as the adafruit-ws2801 package for controlling the LED lights. For extracting motion data from an image, we will be using OpenCV, and for implementing the emergence criterion, we shall use Python bindings to a Java package, JIDT, that implements Information Theoretic Measures.

Finally, we will need to find solutions for deploying a large number of devices running similar software, managing them, and making sure they can be updated with latest packages and configurations. PiServer is a solution for ethernet-connected devices which we can try over wireless. I was unable to find this being done before, but there are many more solutions available which we shall explore when the time comes.

Closing remarks

Nothing like this has been done before, not with humans, and not in the open source community. We are thrilled but anxious to see it work, and we expect many challenges in both implementation and execution.

One of the difficulties posed by measuring emergence of real world systems is identifying the right emergent macroscopic features of the system. In our case, the constraint of maintaining a distance from the other players recalls the avoidance parameter in the Reynolds model, so we could begin by investigating macroscopic features that have emerged from that model, such as the center of mass, as well as direction of average velocity. This is a big theoretical unknown of this project and exciting new science may result from exploring solutions.

Another challenge is deciding how exactly the non-verbal communication occurs, and figuring out if it is enough to drive the game. Here, we take inspiration from swarms of synchronising fireflies. We are interested to see if the players will be able to guide themselves based on the delay or frequency of the blinking lights in order to move as one.

Given the real-time element of the game, another challenge comes from hardware and software latency. The control system needs to be very fast in both computing emergence, and passing messages to the headsets. Moreover, as immersion in the game is crucial to the experience, and as we will be using the system as a platform for novel scientific enquiries, we must make sure the system is very reliable and encounters no critical errors that may interrupt the game or experiment. Therefore, the most exciting, and probably most difficult challenge will be to create a system that is as optimised and reliable as a production system, but using educational tools only.

Implementation instructions for hardware and software will follow in subsequent articles in this series, as we make progress with development and come closer to the first Synch.Live experience! Stay tuned!

Bibliography

Aristotle’s Metaphysics VII (350 B.C.E.) is available here

The research about ant consensus comes from Nigel and Ana Franks’ lab at Bristol Uni. For example, Speed versus accuracy in collective decision making (2003), doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2527. It will be rather interesting to explore in the future whether any blockchain consensus has been inspired by this work.

Craig Reynolds, creator of the boids model, has aggregated a large amount or resources related to flocking systems, Boids, Background and Update, available here. The original paper is Flocks, herds and schools: A distributed behavioral model (1987), doi:10.1145/37401.37406.

The realistic adaptive model for flocking starlings is in Hildenbrandt et al, Self-organized aerial displays of thousands of starlings: a model (2010), doi:10.1093/beheco/arq149

The Vicsek model of particles is actually newer the the boids model by almost a decade. The original paper is Novel type of phase transition in a system of self-driven particles (1995), doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.1226.

The idea of looking for causal emergence in flocking models comes from Anil Seth, Measuring Autonomy and Emergence via Granger Causality (2010), doi:10.1162/artl.2010.16.2.16204

The criterion of emergence is proposed by Mediano, Rosas et al in Reconciling emergences: An information-theoretic approach to identify causal emergence in multivariate data (2020), arXiv:2004.08220. A more extensive exploration of the literature surrounding emergence measures will follow when the time is nigh.

An interesting discussion about crowd modelling can be found at Crowd Behaviour and Psychology